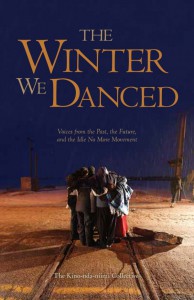

The Winter We Danced: a new book on Idle No More!

The Winter We Danced is a brand-new collection of writing on the Idle No More movement. We at AK Press Distro have been anxiously awaiting getting this new book from our friends at Arbeiter Ring Publishing, ever since we first heard about it. And we weren’t the only ones—we’ve been fielding lots of calls and emails from other folks eager to read the words of the folks involved in this inspiring moment of Indigenous organizing. The waiting is over: the book is here in our hands, and can be in yours too! The publishers were gracious enough to give us permission to post the editors’ introduction to the book here, to give you all a better sense of the book so that you, too, can be excited about it. So here it is, we think it speaks for itself.

—

Idle No More:

Idle No More:

The Winter We Danced

The Kino-nda-niimi Collective

Indigenous peoples have been protecting homelands; maintaining and revitalizing languages, traditions, and cultures; and attempting to engage Canadians in a fair and just manner for hundreds of years. Unfortunately, these efforts often go unnoticed—even ignored—until flash-point events, culminations, or times of crisis occur. The winter of 2012-2013 was witness to one of these moments. It will be remembered—alongside the maelstrom of treaty-making, political waves like the Red Power Movement and the 1969-1970 mobilization against the White Paper, and resistance movements at Oka, Gustefson’s Lake, Ipperwash, Burnt Church, Goose Bay, Kanostaton, and so on—as one of the most important moments in our collective history. “Idle No More,” as it came to be known, was a watershed time, an emergence out of past efforts that reverberated into the future. The clear lesson regarding this brief note of context is that most Indigenous peoples have never been idle in their efforts to protect what is meaningful to our communities—nor will we ever be.

This most recent link in this very long chain of resistance was forged in late November 2012, when four women in Saskatchewan held a meeting called to educate Indigenous (and Canadian) communities on the impacts of the Canadian federal government’s proposed Bill C-45. The 457 pages of multiple pieces of legislation, an “omnibus” of new laws, introduced drastic changes to the Indian Act, the Fisheries Act, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, and the Navigable Water Act (amongst many others). Entitled Idle No More, this “teach-in” organized by Sylvia McAdam, Jess Gordon, Nina Wilson and Sheelah Mclean raised concerns regarding the removal of specific protections for the environment (in particular water and fish habitats), the improper “leasing” of First Nations territories, as well as the lack of consultation with the people most affected even where treaty and Aboriginal rights were threatened. With the help of social media and grassroots Indigenous activists, this meeting inspired a continent-wide movement with hundreds of thousands of people from Indigenous communities and urban centres participating in sharing sessions, protests, blockades and round dances in public spaces and on the land, in our homelands, and in sacred spaces.

From the perspective of our collective and based on the curated articles in this book, the Idle No More movement coalesced around three broad motivations or objectives:

- The repeal of significant sections of the Canadian federal government’s omnibus legislation (Bills C-38 and C-45) and specifically parts relating to the exploitation of the environment, water, and First Nations territories.

- The stabilization of emergency situations in First Nations communities, such as Attawapiskat, accompanied by an honest, collaborative approach to addressing issues relating to Indigenous communities and self-sustainability, land, education, housing, healthcare, among others.

- A commitment to a mutually beneficial nation-to-nation relationship between Canada, First Nations (status and non-status), Inuit, and Metis communities based on the spirit and intent of treaties and a recognition of inherent and shared rights and responsibilities as equal and unique partners. A large part of this includes an end to the unilateral legislative and policy process Canadian governments have favoured to amend the Indian Act.

Admittedly, the movement goes beyond even these issues. The creativity and passion of Idle No More necessarily revealed long-standing abusive patterns of successive Canadian governments in their treatment of Indigenous peoples. It brought to light years of dishonesty, racism and outright theft. Moreover, it engaged the oft-slumbering Canadian public as never before. Within four months, Idle No More moved beyond the turtle’s continental back and became a global movement with manifold demands.

Idle No More is, in the most rudimentary terms, a culmination of the historical and contemporary legacies emerging from colonization and violence throughout North America and the world. These involve land theft, treaty violations, and many misunderstandings. There is therefore much to talk about, reflect upon, and take action to redress. In this way, Idle No More represents a unique opportunity: a chance to deepen everyone’s understanding of the circumstances and choices that have led to this time and place; and a forum for how we can come up with solutions together. This movement represents an important moment for conversations about how to live together meaningfully and peacefully, as nations and as neighbours.

That being said, the nature and enormity of Idle No More meant that it was sometimes bewildering in scope and complexity. As it grew, the movement became broad-based, diverse, and included many voices. There were those focused on the omnibus legislation, others who mobilized to protect land and support the resurgence of Indigenous nations, some who demanded justice for the hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women, and still others who worked hard to educate and strengthen relationships with non-Indigenous allies. Many did all of this at once. Idle No More adopted a radically decentralized character, having no single individual or group “leader.” Instead, communities would join together for distinct purposes, temporarily or for long-term activism. Events were local, regional, and wide-scale. This often confused and frustrated those (particularly in the media) who looked for the “voice” of the movement or somebody who could—or would—speak on behalf of all participants. Idle No More, however, was inherently different. It defied orthodox politics.

Indigenous women have always been leaders in our communities and many took a similar role in the movement. As they had done for centuries when nurturing and protecting families, communities, and nations, women were on the front lines organizing events, standing up and speaking out. Grandmothers, mothers, aunties, sisters, and daughters sustained us, carried us, and taught through word, song, and story. When Indigenous women were targeted with sexual violence during the movement, many of us organized to support those women and to make our spaces safer. Many also strived to make the movement an inclusive space for all genders and sexual orientations and to recognize the leadership roles and responsibilities of our fellow queer and two-spirited citizens. The movement also didn’t escape the heteropatriarchy that comes with several centuries of colonialism. We have more work to do collectively to build movements that are inclusive, respectful, and safe for all genders and sexual orientations.

At almost every event, we collectively embodied our diverse and ancient traditions in the round dance by taking the movement to the streets, malls, and highways across Turtle Island. The powerful events and emotions of the round dance are captured beautifully in SkyBlue Mary Morin’s poem “A Healing Time”—which is why we started off the book in this way. It is also worth remembering how the dance started. Cree Elder John Cuthand explains the origin and significance of the dance:

The story goes there was a woman who loved her mother very much. The daughter never married and refused to leave her mother’s side. Many years later the mother now very old passed away. The daughter’s grief was unending. One day as she was walking alone on the prairie her thoughts filled with pain. As she walked she saw a figure standing alone upon a hill. She came closer and saw that it was her mother. As she ran toward her she could see her mother’s feet did not touch the ground. Her mother spoke and told her she could not touch her. “I cannot find peace in the other world so long as you grieve,” she said, “I bring something from the other world to help the people grieve in a good way.” She taught her the ceremony and the songs that went with it. “Tell the people that when this circle is made we the ancestors will be dancing with you and we will be as one. The daughter returned and taught the people the round dance ceremony.” [1]

In the winter of 2012-2013, our Ancestors danced with us. They were there in intersections, in shopping malls, and in front of Parliament buildings. They marched with us in protests, stood with us at blockades, and spoke through us in teach-ins. Joining us were our relatives, long-tenured and newly arrived Canadians, and sometimes, when we were lucky, the elements of creation that inspired action in the first place.

Speaking of inspiration, the impact of Chief Theresa Spence’s fast on the movement—which many in this book speak about—cannot be understated. We also danced to honour and protect the fasting Ogichidaakwe, who went without food for six weeks on Victoria Island in Omàmìwinini (Algonquin) territory, Ottawa, to draw attention to unfulfilled treaties and the consequences on her community. While originally unrelated to any legislation or to those four Saskatchewan women, her simultaneous protest galvanized the movement. Her commitment provided an urgency that motivated our communities and our leaders to confront the legacy of this colonial relationship. Her sacrifice encouraged so many others to act.

A unique aspect of Idle No More is that the movement often went around mainstream media, emerging in online and independent publications as articles, essays, and interviews. This was the first time we had the capacity and technological tools to represent ourselves and our perspectives on the movement and broadcast those voices throughout Canada and the world—we wrote about the movement while it was taking place. Through social media—but also through good old word of mouth and discussions in lodges and kitchen tables

—these words spread quickly and dynamically, trending through venues like Twitter and Facebook. Never before have Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers and artists presented to Canadians such rich art, stories, and expressive forms to others in such personal, intimate, and dynamic ways that provoke and evoke visions of the past, present, and future. During the winter we danced, the vast amount of critical and creative expressions that took place is like the footprints we left in the snow, sand, and earth: incalculable. And, for the most part, it was full of a positive, creative, and joyful energy that continues to spark critical dialogues.

The Winter We Danced is a collection of much of this important work and a hopeful contribution to the new trajectories of Idle No More and the new movements to come. This book reflects what the movement represents in our history and asks critical questions about the state of Indigenous activism today. More importantly, it also gifts us a look into our future. Like a round dance, readers are invited to reflect upon this beautiful and significant moment, to remember, celebrate, think, and contribute to change we all can benefit from. The Winter We Danced hopes to serve as a space for everyone to join in, and maybe even inspire some more movement.

The Winter We Danced brings together the writings of both actors and activists within Idle No More but also Indigenous and non-Indigenous thinkers, organizers, leaders, artists and advocates—all of whom in various ways are embedded in community and their homelands. We begin with “First Beats”—a group of writing that captures the origins of the movement. “Singers and Dancers” builds upon these beginnings with a series of critical perspectives on core issues and events throughout the movement. “Image Warriors” features some of the most influential and powerful visual art emerging during the movement. “Friendships” reflects our relationships with supporters and allies across lines and borders, while “Next Steps” considers where we might collectively go from here. The resulting volume is an ambitious primer on the history of Idle No More and its implications, but also provides a platform for responses to the movement’s very existence. This collection has been curated by a group of Anishinaabeg and Neyihaw editors who were part of the movement at various stages and, in some cases, helped shape it. We reached out to colleagues and friends in the north, the west and the east to bring their issues and voices into the book. There are, however, some unfortunate absences in the book as a result of time constraints.

Finally, it should be stated that The Winter We Danced is not a complete body of work documenting the movement nor a comprehensive analysis of Idle No More. We have included as many voices as possible from the many who acted and danced and sang and lived in an incredibly diverse movement. At the same time, we have tried to provide a detailed overview of major events over a very complex time. Intended to be read by diverse audiences, this collection is ensconced with distinct politics and perspectives that do not always represent the ideas of all members of the collective. The text will serve as an invitation for those within Indigenous nations, Canada, and elsewhere to learn about Idle No More, reflect on this moment in history, and consider possibilities for the future of Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships. The spirit and the work of the winter we danced continues, like it always has, into the future.

[1] See: creeliteracy.org/2012/12/19/elder-john-cuthand-shares-the-story-of-the-round-dance/

—

You can learn more about the book HERE.